How to write a school research paper in English?

In order to write a school research (scientific) paper in English, you need to manage your time wisely. You need to have six months in reserve to conduct the actual research, as well as time to collect experimental material and reflect on it. Below I will describe the logic of the research paper, which is firmly established in the Western academic tradition. Why is the West an authority? Probably because he calmly showed over a long period how best to create an academic text so that it is as understandable to the reader/consumer as possible. I decided to briefly share this logic here because two teachers independently asked for my advice. It seemed to me that more people might have such questions.

In this note, I will show the structure of the work and explain the logic behind the creation of a research paper - as is customary in the Western tradition. I do not claim completeness of presentation.

Preface. Postulates that must be taken for granted

There are things that you should agree to initially if you want to write a good paper.

First: it's your job. This means that it is shameless to rip tidbits of text from the Internet - taboo; expecting that someone else will write the text for you is taboo; that someone will, in principle, generate ideas for you - taboo. Using someone else's ideas or text without quoting is a crime that in the West cannot wash its hands of until the end of days.

Second: if you want your work to be accepted, understood and appreciated, then it must have a clear structure and contain links to books or scientific (!) articles by authors who have previously dealt with the topic on which you are writing the work. For example, the blog fortee.ru or Wikipedia are not a scientific publication, but the magazine “Foreign Languages in the Republic of Belarus” is, a textbook on English or translation can be (depending on which one, but quoting textbooks in the West is considered frivolous).

Third: the goal of the research work should not be a prize in a competition, otherwise it is a false value. Those. It’s nice to get a prize and it’s worth it, but if you don’t, this is not a reason to be upset or refuse to study.

Part 1. What is a research paper?

A research paper is a text in which the author of the study shows that he studied a certain topic (part of it), studied the material and came to some conclusions that may have (applied/theoretical) significance. The volume of work does not have a fixed number of words: it can be 2500 words (5 A4 pages, 12 Times New Roman), it can be 5000 words (10 pages), or it can be 7500 words (15 pages). The list of sources has no upper limits, but the lower limit is usually 5 sources (at least three of them are scientific). Other types of academic essays (reaction paper, response paper, position paper) or TOEFL essay writing may have their own requirements for academic writing, but I do not cover these topics here.

Part 2. Structure of the research work

The structure of the research work is very simple:

1. Title - the original title should catch attention and also be understandable to the public.

*2. Abstract - a short (up to 250 words) and well-written abstract of the work, which may also contain keywords.

*3. Acknowledgments - words of gratitude to anyone if this someone helped you write your work (moral or financial support, for example).

4. Introduction - an introduction to the work, a brief introduction to the reader about how you came to this topic and why.

*5. Theoretical framework (and Literature overview) - a theoretical framework (and sometimes a literature review) is how you position yourself and your research among the work of other researchers who have already dealt with this topic (and there are always those!). A theoretical framework is a mention of a theory developed by some scientist which you apply in your research work and test whether it works or not. For example, you like the theoretical basis of the Kashkin school of translation (short story: you need to translate the spirit of the work, not specific words), and you choose it as your theory. By doing so, you (a) justify your research and (b) agree with or separate yourself from the theory. For the school level, I believe this is an optional component.

6. Methodology – the way you conducted the research; exactly how you came to the conclusions in your work. The methodology is varied: these can be quantitative methods (for example, a questionnaire or counting statistics) or qualitative methods (for example, interviews, participant observation, ethnography, discourse analysis - usually for written texts). By the way, I have never seen a comprehensive list of research methods anywhere. But this is a very important component of the work. By describing how you reached your conclusions, you show the reader whether he can believe you or not. For example, you are researching translations of movie titles into Russian. In the methodology, it is important to indicate how many movie titles you chose, how many of them had different translations, etc.

7. Body of the research - the main part of the study, which should be divided into parts - sections and subsections. You decide how you will structure your work, what headings you will choose for your sections, and how balanced each section will be in terms of word count.

8. Conclusion – the main conclusions of the study (paraphrased!) and the answer to the question “and then what?”, i.e. why should this concern other researchers on this topic.

An example of a well-structured paper is here (“Can Medication Cure Obesity in Children? by Luisa Mirano”).

Part 3. Logic of introduction and conclusion

In the introduction, the author introduces the reader to the topic he is exploring and narrows it down to a specific problem. The introduction clearly states the research question to which the answer is sought, as well as the main argument , or thesis , of the work . For example, you are interested in the topic of headlines in English periodicals. But this is a wide field for activity. For example, you may be interested in ways to create/write headlines, features of vocabulary in headlines, or features of translating English headlines into Russian. Let's say you chose the last subtopic - translation of newspaper headlines. In the introduction, you should indicate what topic and subtopic you are interested in, why you came to it and how, and what exactly you want to research. The latter is expressed in the research question. For example, it could be like this: “How are British newspaper headings translated into Russian?” Sometimes a number of auxiliary sub-questions are assigned to this question (what is the structure of English newspaper headings? What is the structure of Russian newspaper headings? etc.). The thesis/argument itself should be like an answer to the research question. In our case, it could be, for example, like this: “English newspaper headings should never be translated word-by-word into Russian, because they are different from Russian newspaper headings in spelling, length, grammar, and focus.” In the Western tradition, it is customary for the argument/thesis to appear at the beginning of the text. A good thesis is usually one that can be argued with. Typically, words like “should (not)” turn almost any sentence into a good thesis statement.

The introduction also briefly describes the structure of the work: “Following the introduction, the body of the research paper will focus on the specificities of newspaper headings in English and in Russian as well as on the translation techniques that can be used in rendering English newspaper headings into Russian . In the conclusion, I will answer the research question and discuss the implications of my findings.” If you are wondering whether you can use “I” in academic writing (instead of “we”), the answer is yes. The logic of the introduction is that we lead the reader by the hand through our work and tell him what awaits him next.

The conclusion in large academic works (for example, dissertations) is usually a reflection of the introduction. A paraphrased summary of your main scientific findings. For research work this is not always the case. The conclusion can summarize the content in 2-3 sentences, repostulate in other words your argument/thesis (the culmination of the conclusion), and then answer the main question of the entire work: “So what?” Roughly speaking, what next? What can you do with your findings? How can they be developed further? Some sources write that you can also use the conclusion to indicate the limitations of your work (limitations), they say, due to the small amount of work, I was not able to compare British newspapers with American ones, etc. Or also show what exactly can be further researched on this subtopic (the so-called send-off), for example (and I’m writing this now from the point of view), “It would be a matter of further research to study how English newspaper headings were translated into Russian in the 19th century, since it may give a clue as to why we translate them differently today.”

Part 4. Logic of the main part of the work

Each section in the body of the paper should contain one big idea, which in turn should support your argument/thesis. For example, if you are dealing with the specifics of translating English newspaper headings into Russian, then you can write it in three sections: (1) The structure of English newspaper headings, (2) The structure of Russian newspaper headings, (3) The ways of translating English newspaper headings into Russian.

Sections can have subsections (they can also have their own names). For example, the first section could be thought out in more detail: (a) English headings are short, (b) English headings use “incomplete” grammar, (c) English headings catch and/or shock the reader, (d) English headings are rhythmic. And so on with the other two sections.

This is the so-called minimum work plan - outline. I made it a rule to assign a certain number of words for each part of the work. For example, if the work limit is 5000 words, then I distribute the words offhand as follows: introduction - 300 words, theoretical framework and methodology - 200 words, conclusion - 300 words, main part - 4100 words (section 1 - 800 words, section 2 - 800 words , section 3 – 2500 words). As practice shows, I never write within the given volumes, I always write more and then suffer, trying to remove extra phrases from the text (and there are always extra phrases).

Part 5. Paragraph logic

Let's say we decide to write the first section of the main part of our work. One thing to remember is that each paragraph should have only one idea that supports the main idea of the section. Paragraphs must be ideologically connected to each other. Each paragraph is also built according to its own small structure (which copies the general structure of the work): the first sentence is the key one and says what exactly the author is trying to say in this paragraph. In an ideal academic text, the reader should be able to read only the first sentences of each paragraph in order to understand what the section is about and, therefore, what the entire research paper is written about. The first sentence of a paragraph is the essence of the entire paragraph, everything else is support for this idea and analysis (the most difficult part, in my opinion).

Let’s say we are studying translations of English headings and for the first section we decided to write 6 paragraphs: 1 – introductory, 2 – about the brevity of English headings, 3 – about the “crooked” grammar of English headings, 4 – about the special function of English headings, 5 – about the rhythm of English headings, 6 – final and general paragraph for this section. Let's see how we can, for example, outline the second paragraph (#2 is about brevity).

The first sentence should be topical, for example: “Newspaper headings in English periodicals are very concise and crisp.” This is the so-called our small argument, which we will expand further. And then we need to provide evidence that this is so. Here it is advisable to use links to other authors who have dealt with this topic. You can also use your own research, for example (again, this is crazy): “According to a Russian linguist Fyodorov, newspaper headings in English tend to be between 4 and 9 words, and if a journalist needs more words, he or she tends to use subheadings (Fyodorov, 1956, p. 87). In the 15 articles that I analyzed on the BBC website in the section 'Science,' most headings had a maximum of 6 words." Those. we have provided evidence to support our thesis in the first sentence. But this evidence itself does not say anything. As they say, so what next? Well, yes, you noticed that the headings are short, but why is this important? Why is this important for translation into Russian, if your work is about translating headlines into Russian? And here you need to further write your analysis - what does this mean for the overall picture or for the universe. This part is entirely the thoughts of the author of the article, i.e. yours. The analysis is yours, this is the whole value of the work: you share what your brain has produced. In this case, you can write, for example, the following: “This suggests that the attention of readers can be much more easily grasped by fewer words—as few as an eye can catch without any movements.” The shorter the word, the more likely a reader will notice the article and eventually read it through. Short headings allow journalists to win their readers.” In principle, this is similar to analysis. Those. what follows after we notice some feature.

And then - the next paragraph, the next subtopic. Of course, paragraphs must be entered wisely and carefully; they must also be interconnected and confirm the main idea of the section. You need to use transition words correctly (therefore, consequence, first, second, third, in addition, also, furthermore, etc.). The reader must flow with us through our text. We must always think about the reader of our work, even if it is only our teacher.

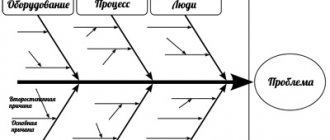

The logic of an academic text can be schematically represented in the following diagram (see picture). This is the ideal, of course.

Scheme. Logic of academic text. Each “detail” supports the main idea, and the main idea supports the main argument/thesis.

For further reading :

The Purdue Online Writing Lab, https://owl.english.purdue.edu/

The American Psychological Association Style (APA Style), https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/664/01/

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter.

“Project and research activities in English lessons”

“Project and research activities in English lessons”

Stesikova Svetlana Gennadievna,

English teacher MBOU Secondary School No. 58, Arzamas

Research competence is a body of knowledge in a certain field, the presence of research skills (seeing and solving problems based on putting forward and justifying hypotheses, setting goals and planning activities, collecting and analyzing the necessary information, choosing the most optimal methods, performing an experiment, presenting research results, ) the ability to apply this knowledge and skills in specific activities.

A. V. Khutorskoy

Today, modern society needs educated, creative, active young people and makes a social order for the formation of a literate and socially mobile personality. Life itself puts forward an urgent practical task - the education of a creative person, creator and innovator, capable of solving emerging social and professional problems in an unconventional, proactive and competent way.

The role of the teacher

A prerequisite for the development of students' creative abilities is the elimination of the dominant role of the teacher. The most difficult thing for a teacher is to learn to be a consultant. It's hard to resist the hints. But it is important during consultations only to answer questions that students have.

The role of the teacher is different at different stages of organizing research activities.

Stage I. Diagnostics. Identification of children predisposed to research work. The role of the teacher is dominant. The interaction between teacher and students is close.

Stage II. Defining the topic, goals, setting tasks. At this stage, the teacher already acts as a consultant. The role of the teacher is not dominant.

Stage III. Completing of the work. The teacher is a consultant. The student is given maximum independence.

Stage IV. Protection (activity analysis). At this stage, the teacher and student(s) are equal partners.

The work begins with identifying students who have the inclination and desire to engage in research activities. A big role in this is played by subject teachers and parents, who know the capabilities and aspirations of students better than anyone and can help them with advice and action.

At the next stage, specific projects are identified and work leaders are selected, who are school teachers. Based on the analysis of the activities of the scientific society of students, the following motives of students to engage in research work were identified: interest in the subject; the desire to deepen your knowledge and broaden your horizons; connection with future profession; satisfaction with the work process; desire to assert oneself; receive an award at a competition; enter university; and others.

Selecting a project topic.

Work on a research project begins with the choice of a topic, although its formulation does not appear immediately. What determines the choice of topic? Practice shows that this is due to what is most interesting to the student, or to the fact that he has suitable material for research. Sometimes the topic is chosen on the advice of teachers or parents. Choosing a research topic is a difficult moment. Sometimes students propose topics that are clearly beyond their capabilities. Often the topics are abstract in nature. And it happens that the topic is interesting, but there is not enough material for research. And here the student needs advice from a teacher.

Planning and organizing work on the project.

The success of an activity largely depends on its clear organization. Under the guidance of the teacher, a schedule for completing educational research is drawn up: the time frame, volume of work and stages of its implementation are determined. During the work, many things present significant difficulties for students:

— identification of the research problem;

— setting goals and objectives, defining the object and subject of research;

— correct choice of research methodology, conducting an experiment;

-selection and structuring of material;

— compliance of the collected material with the topic and goals of the study.

Basic requirements for using the project method

1. The presence of a problem / task that is significant in research, creative terms, requiring integrated knowledge, research search for its solution (for example, research into the history of the celebration of various holidays in English-speaking countries - St. Patrick's Day, Thanksgiving Day, Halloween, Christmas, Mothers ' Day, etc; organizing travel to different countries; family problems, the problem of free time for young people, the problem of home improvement, the problem of relations between generations, the problem of organizing sporting events, many others);

2. Practical, theoretical significance of the expected results (for example, a report to the relevant services on the demographic state of a given region, factors influencing this state, trends in the development of this problem; joint publication of a newspaper, almanac with reports from the scene; tourist route program , plan for arrangement of a house, park, plot, layout and arrangement of an apartment, etc.);

3. Independent (individual, pair, group) activities of students in class or outside of class time.

4. Structuring the content of the project (indicating stage-by-stage results and distribution of roles).

5. Use of research methods: identifying the problem, the research tasks arising from it, putting forward a hypothesis for their solution, discussing research methods, drawing up the final results, analyzing the data obtained, summing up, adjusting, conclusions (using the “brainstorming” method during joint research, “round table”, creative reports, project defense, etc.).

Types of research activities in the classroom

1. Project method. Group representatives prepare reports on topics. Students with poor preparation have the opportunity to use the suggestions of the substitution table when composing their short statement.

2. Laboratory work. In particular, in English lessons you can conduct a number of laboratory works. How to write a correct question in English? Word order in an English sentence.

3. Case technologies. Case method or case technology (learning based on specific cases). The essence of this method of teaching is that students are offered specific situations, which are discussed in class and serve as the basis for further research activities.

The project is the main form of research activity for high school students; it connects theory and practice, which is important for students. The project method is based on the student’s existing experience, his own path of searching and overcoming difficulties. The project method is one of the effective means of preparing students for research activities in English lessons and, in addition to potential creative abilities, capabilities and erudition, it requires independence from the student, the ability to think problematically and certain, still poorly formed research skills. The project method is based on the student’s existing experience, his own path of searching and overcoming difficulties.

Examples of lesson-based educational and research activities: lesson projects, problem-based lessons, practical and laboratory classes (when laboratory work is performed by students of the whole class at the same time, all together), composing sentences, solving crossword puzzles, replacing words, filling in the blanks.

Examples of extracurricular educational and research activities are: abstract work, project work based on interests, educational and research work, scientific work, olympiads, conferences. Unified State Exam.

Effectiveness of work in educational research technology.

The goal of teaching a foreign language is the communicative activity of students, i.e. practical knowledge of a foreign language. The teacher’s task is to intensify the activity of each student, to create situations for their creative activity in the learning process. The use of new information technologies not only enlivens and diversifies the educational process, but also opens up great opportunities for expanding the educational framework, undoubtedly carries enormous motivational potential and promotes the principles of individualization of learning. Project activities allow students to act as authors, creators, increase creativity, expand not only their general horizons, but also contribute to the expansion of language knowledge.

Bibliography:

1. Belova S. A. Technology of research activities in a foreign language in teaching students - https://image.websib.ru/05/

2. Dusheina T.V. “Project methodology in foreign language lessons.” Institute of Nuclear Sciences, 2003, No. 5.

3. Koptyug N.M. “Internet project as an additional source of student motivation.” Foreign languages at school, 2003, No. 3.

4. Novikova T. Design technologies in lessons and extracurricular activities. //Public education, No. 7, 2000, pp. 151–157

5. Pavlenko I.N. “Use of project-based methodology in teaching children of senior preschool age.” Institute of Nuclear Sciences, 2003, No. 5.

6. Podoprigorova L.A. “Use of the Internet in teaching foreign languages.” Institute of Nuclear Sciences, 2003, No. 5.

7. Features of organizing research work with high school students in a foreign language - https://www.tgl.net.ru/wiki

8. Savchenko N. A. Project method in teaching English to secondary school students. — https://www.ioso.ru/distant/library

9. Sergeev I. S. How to organize project activities of students: A practical guide for employees of educational institutions. - M.: ARKTI.2006.